This post has been written by Founding Editor Mallika Sen.

Last week, the Indian Finance Minister, Piyush Goel announced a new, five-pronged strategy to ‘strengthen’ the banking system, aptly titled, ‘Project Sashakt’, proposed by a high-powered committee led by the Chairman of the Punjab National Bank, Sunil Mehta. This is just the latest in a series of measures undertaken by the Government to tackle India’s mounting bad loan problem, the most notable of these measures being the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC).

This post first briefly outlines the three resolutions strategies that are proposed under Project Sashakt. Thereafter, it looks into the third proposed strategy, that is, resolution through asset management companies (AMCs) in detail. It analyses the legal framework within which the AMCs are to operate, and whether or not regulation in the implementation of Project Sashakt is ideal.

What is Project Sashakt?

Project Sashakt is a resolution strategy targeted at tackling the Indian banking system’s ever-increasing NPAs. It lays down three different resolution approaches, the applicability of each of which is contingent upon the value of NPAs.

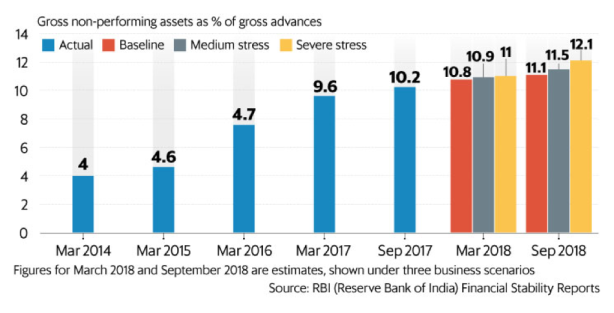

Fig. 1- A Steady Increase in Bad Loans Held by Indian Banks

Fig. 1- A Steady Increase in Bad Loans Held by Indian Banks

Bad loans up to ₹50 crore (Category I) are to be managed at the bank level itself, within a prescribed 90-day deadline. In the case of bad loans between ₹50-500 crores (Category II), Project Sashakt proposes a system of an inter-creditor arrangement (ICA) wherein NPAs are tackled by a consortium of banks created by all lenders signing a legally binding agreement to the effect, resulting in a participatory process of NPA resolution. This process is subject to a 180-day deadline. In this system, most decisions related to NPAs are transferred to the lead lender. This, however, has given rise to some concerns about narrow concentration of power in the hands of a few big lenders (for instance, SBI is the lead lender in 60% of bad loan cases), to the detriment of smaller banks within the consortium.

In India, the total value of bad loans worth ₹500 crore or more is estimated to be around Rs. 3 trillion. Thus, the most important, high-stakes resolution approach under Project Sashakt, is the one proposed for bad loans of a value greater than ₹500 crore (Category III). In the case of such high-value NPAs, the project proposes the setting up of an independent Asset Management Company (AMC), constituted by several sector-specific Alternate Investment Funds (AIFs). In this model, the various AIFs, through the AMC will bid for the stressed assets, and be responsible for the turnaround of the stressed asset. On completion of the bidding process, the AMC will transfer ownership of the stressed asset to the successful bidder (AIF), who will hold at least a 76% stake in the asset. If resolution is not possible under any of the three proposed strategies, then IBC, 2016 is to kick in.

What We Know About the Regulatory Framework of Project Sashakt

In India, in the post- IBC era, there is a designated regulator for insolvency proceedings, that is, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI). While the corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP) under the IBC has a resolution professional in- charge and a demarcated committee of creditors, the IBC makes it clear that the IBBI has a clear regulatory role in the entire process.

In the case of Project Sashakt, there is no clarity regarding what kind of regulatory framework it will function within. Generally, asset reconstruction companies should be considered within the purview of bodies governed by the IBC, on account of the role they perform in an insolvency process. When taken to its logical conclusion, this also implies that AMCs under project Sashakt would be subject to regulatory oversight by the IBBI.

However, from what is known about Project Sashakt so far, it appears that the primary thrust of the Government is with respect to participatory arrangements and self-regulation. In fact, it has been made clear that the resolution mechanisms under the project are intended to be subjected to minimal interference by the government or regulatory authorities.

To Regulate or not to Regulate?

A regime of minimal regulation as what appears to be envisaged is not ideal for the most effective implementation of Project Sashakt. There are two primary reasons for the same.

First, although AMC/ ARCs have existed for a reasonable period of time, they have largely been unable to make any sort of notable dent in India’s bad loan problem. However, it is likely that bringing AMCs under the ambit of a so-called ‘tough law’ like the IBC and making them subject to the scrutiny of the IBBI may spur efficiency in the AMC model itself, pushing the success of Project Sashakt.

Secondly, a more involved regulatory framework is of imperative importance, because the project, as it presently exists leaves a very large scope for potential litigation before the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT), or perhaps the Debt Recovery Tribunal. This is far from ideal because the NCLT is already burdened with cumbersome litigation relating to the CIRP under the IBC. Thus, it is necessary to minimize the window of permissible litigation, which is best- achieved through a stronger regulatory framework.

For one, at present, the proposal itself provides that if the proposed timeline of 180 days for Category II resolutions is not met, the case is to be transferred to the NCLT. Judging by the precedent of non-adherence to the strict timelines in the IBC cases presently undergoing resolution, it seems unlikely that banks acting in a consortium will meet the 180-day deadline. This will result in the dumping of a large number of cases before the NCLT.

Moreover, under the ICA, an independent committee is envisaged to oversee the resolution of independent account of bankers. However, there is still not much clarity, beyond the requirement of a majority vote for the passing of a resolution plan, on the rights that will be guaranteed to smaller banks in the consortium. The Government has made clear that the ICA arrangement is intended to be participatory and self-regulatory. In such a scenario, the lack of a robust regulatory mechanism can potentially result in two detrimental outcomes. First, disputes within the consortium itself (for instance, on how steep a haircut to agree to) may lead to further delays in the resolution process, and secondly, disgruntled smaller bankers with a minority vote may choose to contest the resolution plan which is finally approved, leading to further litigation.

Conclusion

While it would be unfair to characterize Project Sashakt as a misstep in the larger banking agenda of the resolution of bad loans, from what is presently known, it does appear to exist in a vacuum of sorts. Project Sashakt has not been formally brought within the purview of the IBC and is primarily to be participatory and bank-led, with minimal government or regulatory interference. Given the grim estimates of bad loans on the balance sheets of Indian banks and the lack of effectiveness of bank-led measures in the past, it would be prudent to bring Project Sashakt within a regulatory framework. Admittedly, the IBC is a tough law and it may not be ideal to bring all bad loans, even those of smaller values within the IBC framework, but it is certainly necessary for the process to have some regulatory processes. Thus, regulatory control exercised by the IBBI over AMCs constituted under Project Sashakt would go a long way in furthering the effective implementation of this project.